Moving On

Once upon a time, before the iPhone, before Facebook, before Hurricane Katrina, back when George W. Bush was still President, I plead guilty in both state and federal court to a boatload of charges including armed robbery and possession of a firearm by a convicted felon. I didn’t hurt anyone. Not physically at least. And the sum total of my ill-gotten gains amounted to a couple hundred dollars. Enough for a few more pieces of crack. I would’ve come out better shoplifting at Walmart. Embarrassing to admit that I was once so desperate, so enslaved, so ignorant that I could sink to this level, but it’s part of who I am, part of my story. I own it.

The state sentenced me to twenty years mandatory. The federal government gave me 379 months. Luckily, the sentences were run concurrently. (If there’s anything lucky about receiving 31 years in prison.) I still remember the conversations when I returned to my cell on the sixth floor of Castle Greyskull. “Dude, you signed a deal for all that time? Are you crazy? Thirty years ain’t no deal. That might as well be a life sentence. I would’ve took that shit to trial!”

This was the general consensus. And my fellow inmates had a point. But they didn’t have all the information. The evidence against me was overwhelming—video surveillance, a gun with my prints on it, not to mention my own confession on the night of my arrest. Plus, I was just tired. Weary. The free world was apparently not for me. I had already served from ages 18 to 28 in prison and upon my release I quickly became hooked on crack, crashed multiple cars, received 70 staples in my head, mangled every relationship I had, got mutilated by police K-9s, and lost everything. My friends, my girl, my self-respect. I was ready to lay down.

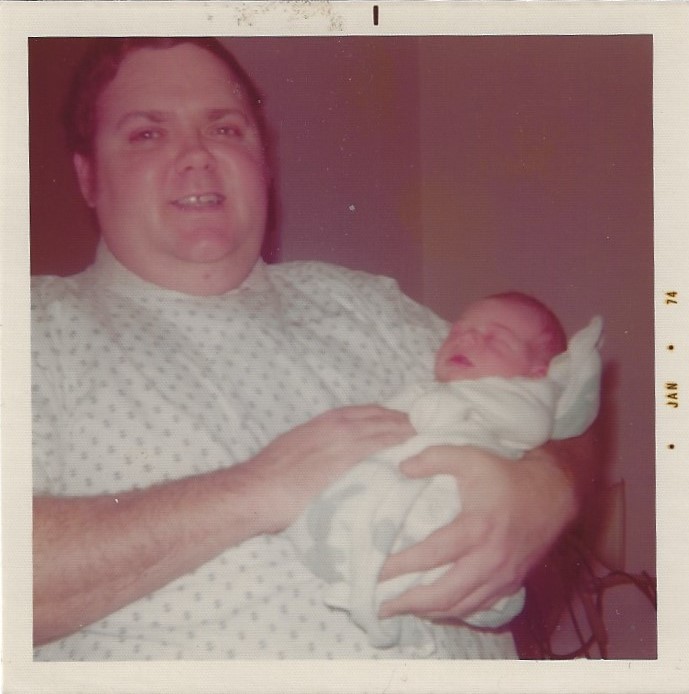

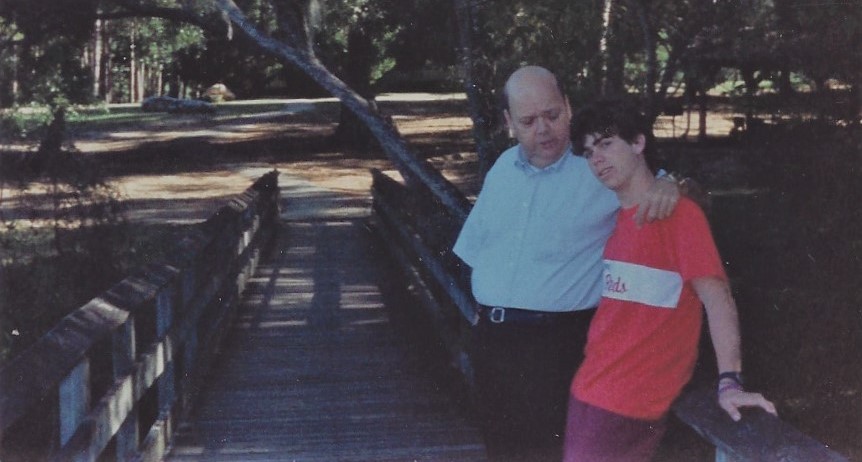

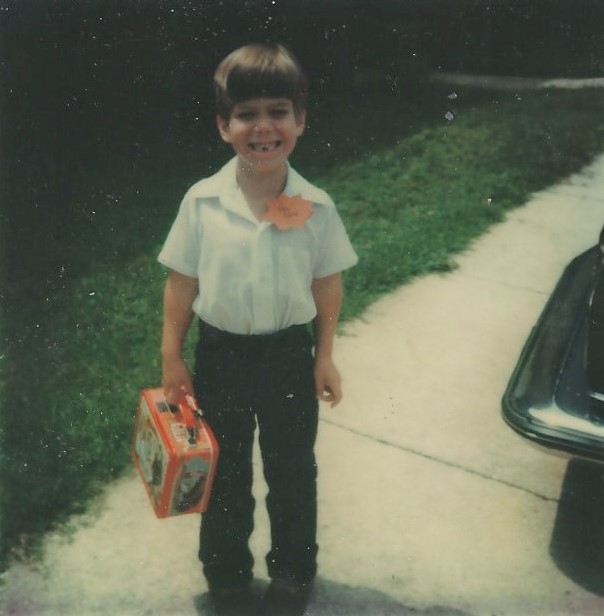

And then there was mom. The sweet lady who never missed a court date, never missed a visit, never stopped believing in me. Arguably the victim who has suffered most from my crimes. She was 58 at the time. If I could make it home in 30 years, she would be in her 80s. Maybe I could cut her grass, work in her garden, clean her drainpipes, take care of her when she was old and needed me. One last shot to come through for her the way she always came through for me. One last chance to do something honorable and reciprocate the unconditional love that has been shown to me my entire life.

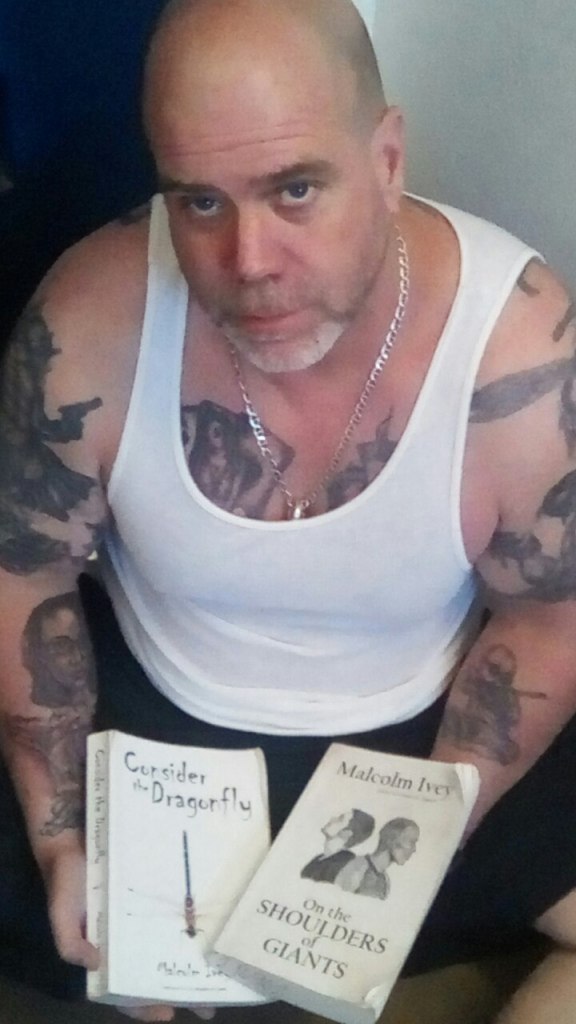

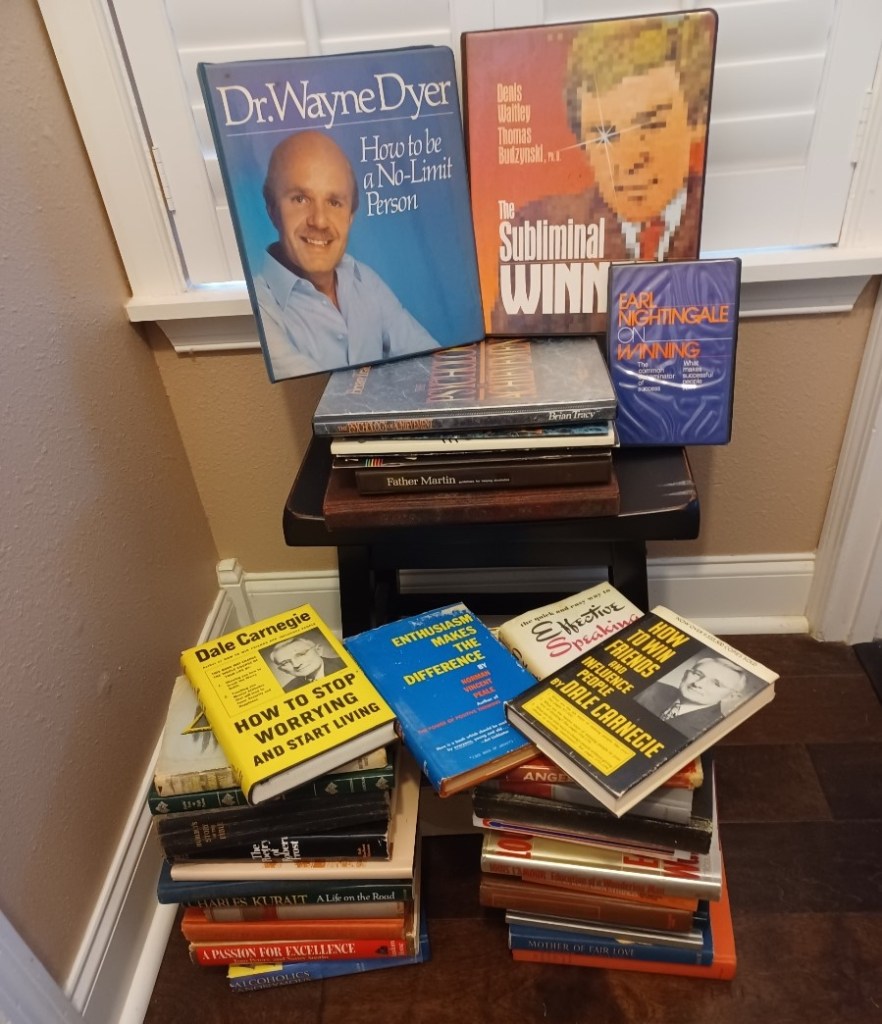

So I copped out. All those years ago. And for close to a couple decades I’ve been doing my time like it was a life sentence, but with a happy ending. I don’t do calendars. Never have. And I don’t pay much attention to my release date. I just look forward to the next visit, the next football game, something in the very near future. Every once in a while, I’ll raise the periscope and scan the horizon. When I passed the ten-year mile marker it was a noteworthy event. But I still had close to another decade to do in state prison plus a 2032 release date in the federal system. Then, in 2016, a Supreme Court ruling rendered an enhancement of my sentence illegal, and my fed time was dropped from 379 months to 288 months (24 years!). This meant that once I finished my state bid, I’d only have a couple years to do in the feds. Time marched on. Visit by visit, book by book, year by year. Since my state sentence was twenty mandatory, the release date on my monthly gain time slip never changed: 10/25/2023. This was the first finish line. When Sticks & Stones came out in early 2018, I had five years and nine months left to serve. “Five and some change.” When Year of the Firefly was released, I had two years and some change. Weight of Entanglement (2022) was a year and some change. And ever since October of last year, it’s just been “some change.”

I still try not to pay much attention. I keep my head down, work on these books and essays, look forward to another Saturday eating microwave food and drinking coffee with mom, another Sunday of Miami Dolphins football. I’ve still got a little fed time left to do before I make it home. But I just slipped under the 30-day mark in state prison. Pocket change.

The finish line is in sight.

I’m moving on.