Six Pages

“The imagination, like certain wild animals, will not breed in captivity . . .” George Orwell, author of 1984, wrote these words. And while Mr. Orwell was damn near clairvoyant when it came to the dystopian future and the rise of the totalitarian state, I have to disagree with him on this point.

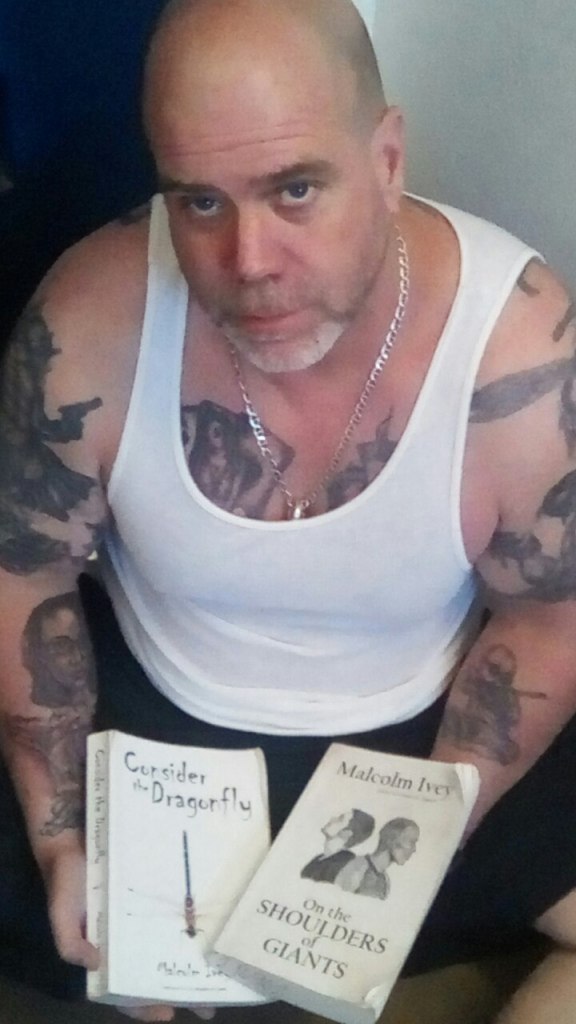

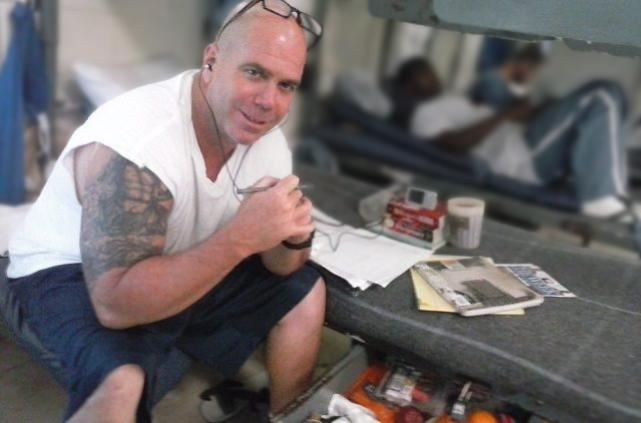

I’ve been living in captivity for most of my adult life and writing books from cramped cells and steel bunks for the last 15 years. During the most bleak and psychologically oppressive periods of this journey, it was my imagination that kept me company and filled me with hope. Without my imaginary friends and the parallel worlds they inhabit, I’d be crazy by now. “Nuttier than squirrel shit,” as a character from one of my first books once said.

Now that I’ve arrived at the dwindling hours of a 7,550 day odyssey that began in March of 2005 and wound its way through eight books, six presidential terms, and half the prisons in the Florida Panhandle to the crumbling Indiana federal dungeon where I sit drafting this final E=mc2 newsletter on a November afternoon in 2025, it seems like a good time to allow myself to let off the gas and peek in the rearview.

When I began writing my first novel, Consider the Dragonfly, in early 2011, the Florida Department of Corrections was the most dysfunctional prison system in the U.S. Its aging institutions were understaffed, unairconditioned (they still are), teeming with scabies and staph, oblivious to basic human needs like nutrition or even a reliable supply of toilet paper, and rampant with abuse. I had recently finished serving nine months on 24-hour lockdown for an alleged relationship with a staff member. I weighed 132 pounds and was having major breathing difficulties even though I quit smoking while I was in the hole. For some reason, that deep satisfying breath that I had taken for granted my entire life was suddenly elusive. I was convinced it was asthma or COPD, but after checking my blood oxygen level repeatedly and finding nothing wrong, the nurse told me it might be anxiety. In hindsight, this makes total sense. Especially considering the conditions.

What made me want to write a book in the first place? I’m not sure. I have numerous theories—and I’ve mentioned most of them in various essays over the years—but no concrete answers. Here are a few of the greatest hits:

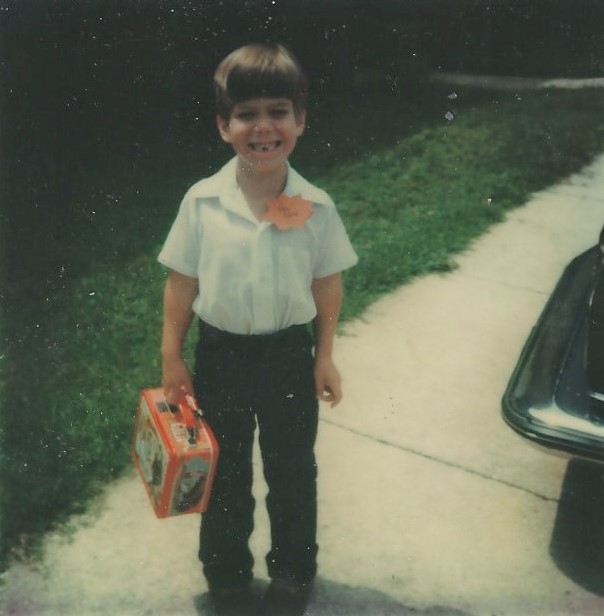

- Age 40 was rapidly approaching and I had nothing to show for my time on Planet Earth—no kids, no property, no retirement account . . . just a criminal record dating back to the juvenile justice system in the late ’80s.

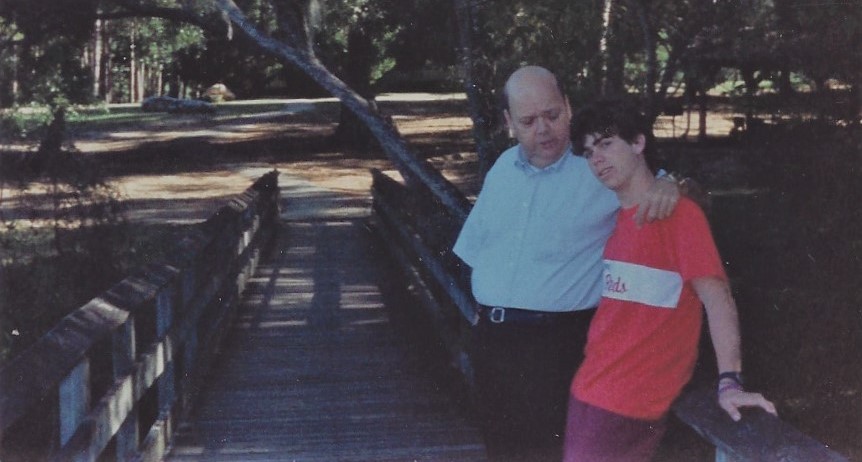

- I spent my whole life breaking mom’s heart and letting her down. I wanted to give her something to be proud of.

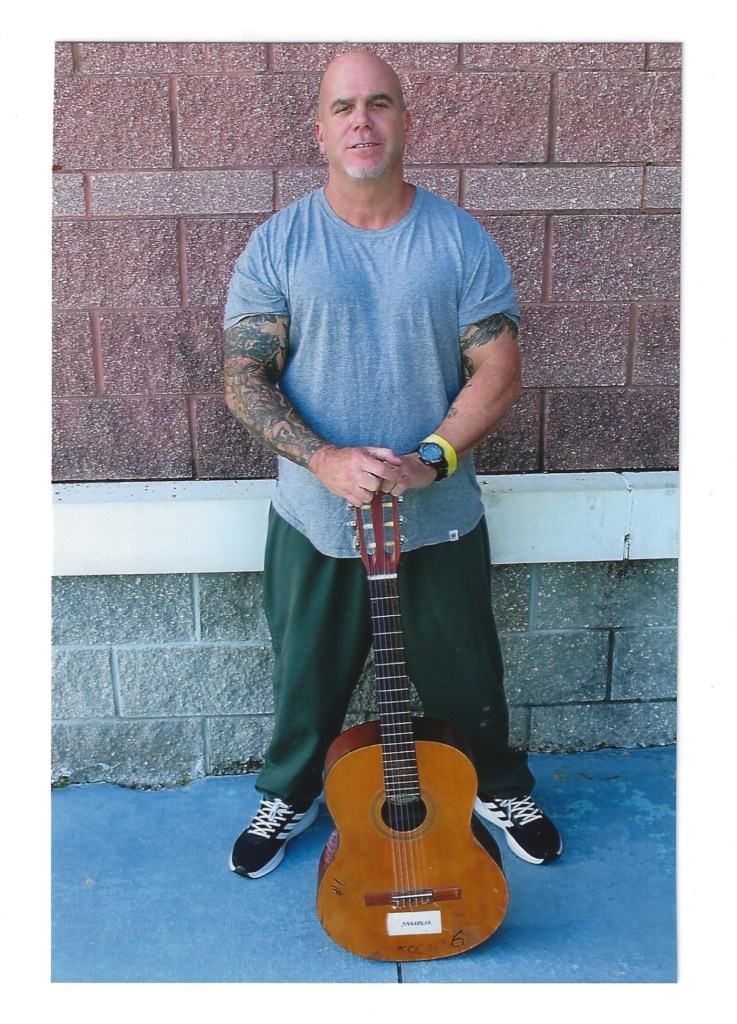

- I was a musician with no instrument. No guitar. But the creative impulse within me could not be suppressed and ended up working its way out through fiction.

- Similar to the character of Izzy in my third novel, On the Shoulders of Giants, I was seeking an identity other than failure, loser, career criminal.

- I grew tired of writing unanswered letters to disinterested people, so I decided to write the world a letter in the form of a book.

All of these motivations are true. Then and now. In 2024’s Letters to the Universe, I offered a more metaphysical explanation:

There’s a passage near the end of Liz Gilbert’s magisterial Eat Pray Love where she riffs on a Zen school of thought regarding the oak tree. In her retelling, the mighty oak is brought into being by two separate forces at the same time: the obvious one, the acorn, but also something else—the future tree itself which wants so badly to exist that it pulls the acorn into being.

All those letters, all those years. All of the working and reworking of sentences and paragraphs, trying to make them sing, replacing weak verbs with more robust options, attempting to convey humor, expanding my limited vocabulary, learning to write like I talk . . . Maybe what I was actually doing was finding my voice, shaping it, sharpening it, letter by letter, year after year. Maybe, like Liz Gilbert’s mighty oak, a grizzled fifty-year-old convict and multi-published author was pulling his twenty-year-old self forward, willing him to “Grow! Grow!” all this time.

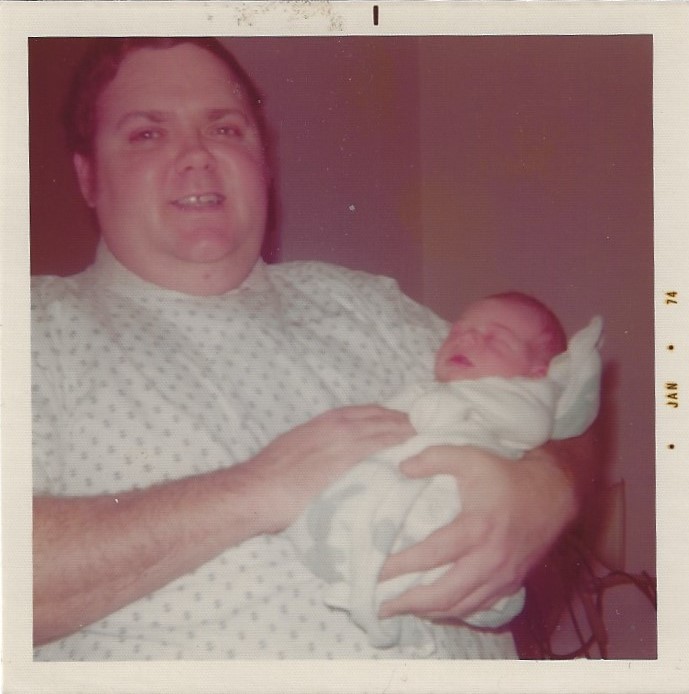

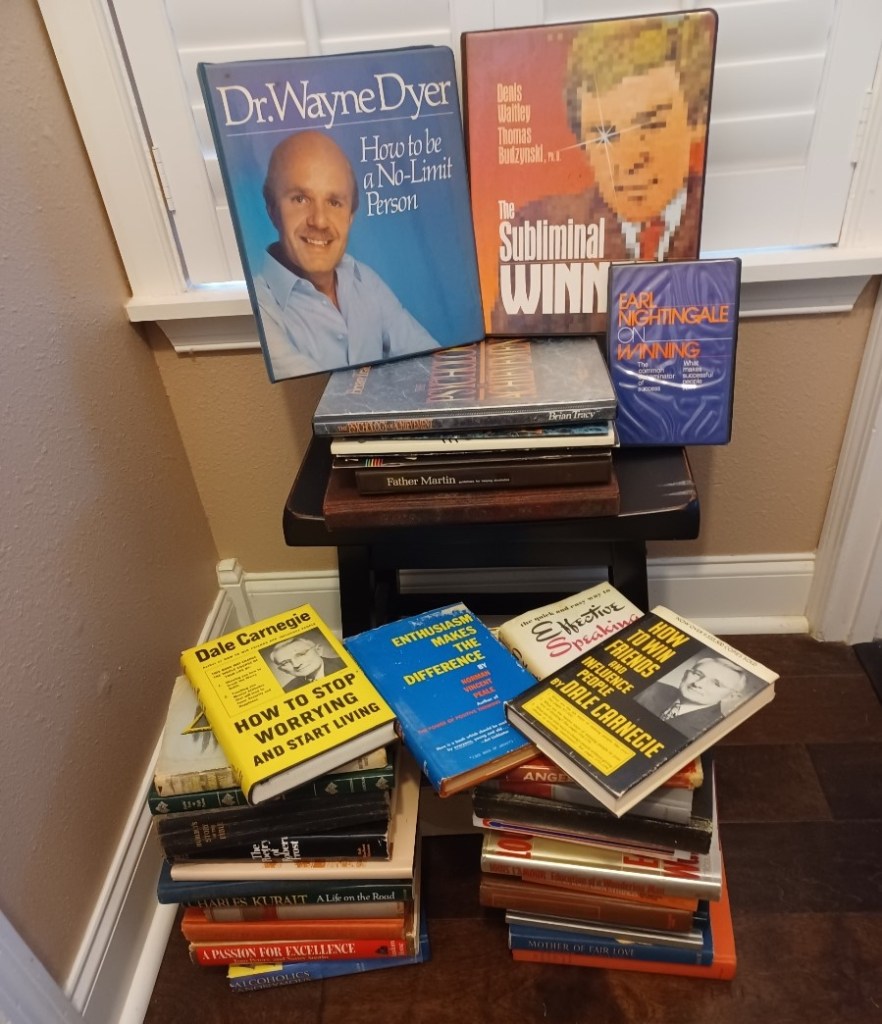

And so, with the centrifugal pressure of all these forces pushing and pulling and swirling and gathering inside of me, as well as all the fear and suffering and violence surrounding me, I sat down on my bunk, put in my headphones, and began to write the story of CJ McCallister. I had no idea what I was doing. But I did it every day. And slowly, the characters stirred to life. Mom had recently retired after 40 years of administrative assistance in those days and was thrilled that I was doing something with my time other than chasing dope and running parlay tickets. When I asked if she would type my handwritten pages, she agreed without hesitation. But I doubt she ever imagined that this single question would define the next fifteen years.

Ever since that day, I’ve been stuffing pages in envelopes, six at a time, and sending them home. A week or two later, they return to me typed and double-spaced in Times New Roman font and sandwiched between Miami Dolphins articles and letters about the birds in the backyard. This is still happening today, even though mom is nearing 80 years old and I’m a couple weeks away from going home. In fact, I just received the latest installment of Prose for Cons in the mail last night.

Process. In James Clear’s Atomic Habits, he notes that “we don’t rise to the level of our goals, we fall to the level of our systems.” This system that we installed 15 years ago is still humming along today. It’s a system that turned adversity into hope, and weakness into strength. Six pages at a time. There’s a lot of talk in writer circles about AI replacing human authors. But the journey of how these particular books were written could never be replicated by a machine. The next time you hold a Malcolm Ivey novel in your hands, I hope you will remember this.

—November 2025