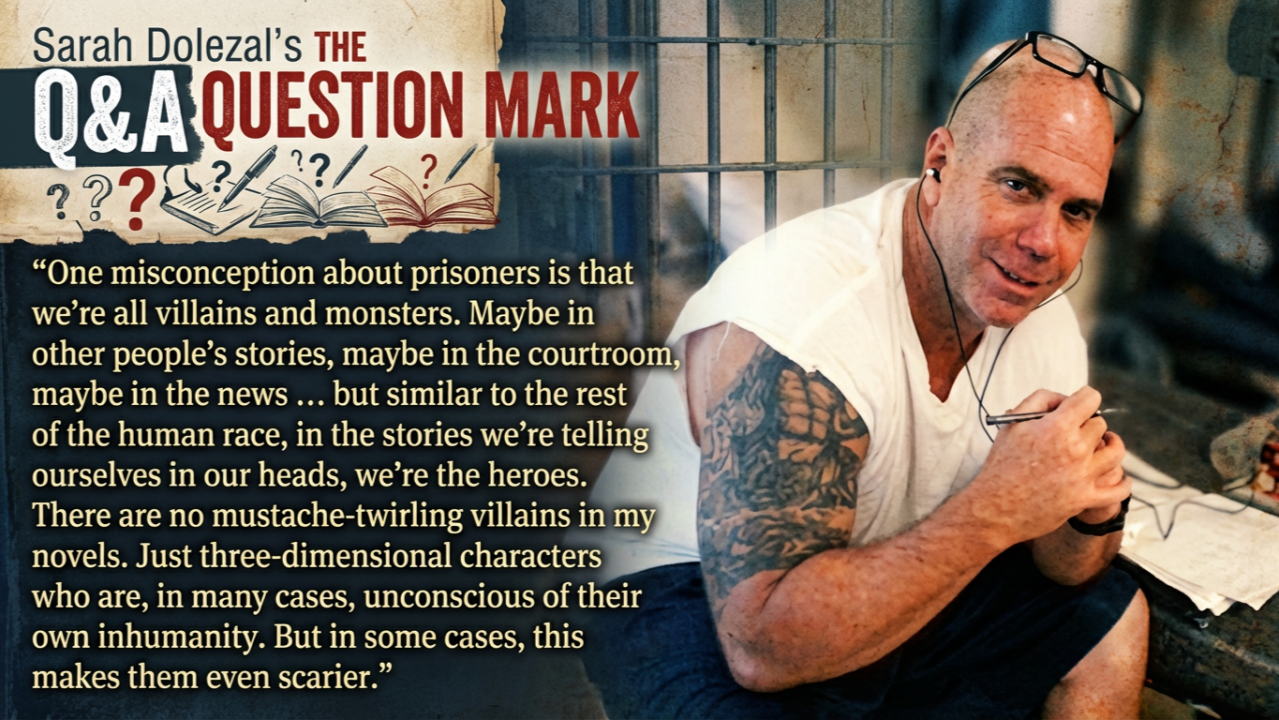

Interview with Sarah Dolezal

Just did this interview with freelance journalist Sarah Dolezal in The Question Mark: Expert Q&A. Momentum!

Just did this interview with freelance journalist Sarah Dolezal in The Question Mark: Expert Q&A. Momentum!

“The imagination, like certain wild animals, will not breed in captivity . . .” George Orwell, author of 1984, wrote these words. And while Mr. Orwell was damn near clairvoyant when it came to the dystopian future and the rise of the totalitarian state, I have to disagree with him on this point.

I’ve been living in captivity for most of my adult life and writing books from cramped cells and steel bunks for the last 15 years. During the most bleak and psychologically oppressive periods of this journey, it was my imagination that kept me company and filled me with hope. Without my imaginary friends and the parallel worlds they inhabit, I’d be crazy by now. “Nuttier than squirrel shit,” as a character from one of my first books once said.

Now that I’ve arrived at the dwindling hours of a 7,550 day odyssey that began in March of 2005 and wound its way through eight books, six presidential terms, and half the prisons in the Florida Panhandle to the crumbling Indiana federal dungeon where I sit drafting this final E=mc2 newsletter on a November afternoon in 2025, it seems like a good time to allow myself to let off the gas and peek in the rearview.

When I began writing my first novel, Consider the Dragonfly, in early 2011, the Florida Department of Corrections was the most dysfunctional prison system in the U.S. Its aging institutions were understaffed, unairconditioned (they still are), teeming with scabies and staph, oblivious to basic human needs like nutrition or even a reliable supply of toilet paper, and rampant with abuse. I had recently finished serving nine months on 24-hour lockdown for an alleged relationship with a staff member. I weighed 132 pounds and was having major breathing difficulties even though I quit smoking while I was in the hole. For some reason, that deep satisfying breath that I had taken for granted my entire life was suddenly elusive. I was convinced it was asthma or COPD, but after checking my blood oxygen level repeatedly and finding nothing wrong, the nurse told me it might be anxiety. In hindsight, this makes total sense. Especially considering the conditions.

What made me want to write a book in the first place? I’m not sure. I have numerous theories—and I’ve mentioned most of them in various essays over the years—but no concrete answers. Here are a few of the greatest hits:

All of these motivations are true. Then and now. In 2024’s Letters to the Universe, I offered a more metaphysical explanation:

There’s a passage near the end of Liz Gilbert’s magisterial Eat Pray Love where she riffs on a Zen school of thought regarding the oak tree. In her retelling, the mighty oak is brought into being by two separate forces at the same time: the obvious one, the acorn, but also something else—the future tree itself which wants so badly to exist that it pulls the acorn into being.

All those letters, all those years. All of the working and reworking of sentences and paragraphs, trying to make them sing, replacing weak verbs with more robust options, attempting to convey humor, expanding my limited vocabulary, learning to write like I talk . . . Maybe what I was actually doing was finding my voice, shaping it, sharpening it, letter by letter, year after year. Maybe, like Liz Gilbert’s mighty oak, a grizzled fifty-year-old convict and multi-published author was pulling his twenty-year-old self forward, willing him to “Grow! Grow!” all this time.

And so, with the centrifugal pressure of all these forces pushing and pulling and swirling and gathering inside of me, as well as all the fear and suffering and violence surrounding me, I sat down on my bunk, put in my headphones, and began to write the story of CJ McCallister. I had no idea what I was doing. But I did it every day. And slowly, the characters stirred to life. Mom had recently retired after 40 years of administrative assistance in those days and was thrilled that I was doing something with my time other than chasing dope and running parlay tickets. When I asked if she would type my handwritten pages, she agreed without hesitation. But I doubt she ever imagined that this single question would define the next fifteen years.

Ever since that day, I’ve been stuffing pages in envelopes, six at a time, and sending them home. A week or two later, they return to me typed and double-spaced in Times New Roman font and sandwiched between Miami Dolphins articles and letters about the birds in the backyard. This is still happening today, even though mom is nearing 80 years old and I’m a couple weeks away from going home. In fact, I just received the latest installment of Prose for Cons in the mail last night.

Process. In James Clear’s Atomic Habits, he notes that “we don’t rise to the level of our goals, we fall to the level of our systems.” This system that we installed 15 years ago is still humming along today. It’s a system that turned adversity into hope, and weakness into strength. Six pages at a time. There’s a lot of talk in writer circles about AI replacing human authors. But the journey of how these particular books were written could never be replicated by a machine. The next time you hold a Malcolm Ivey novel in your hands, I hope you will remember this.

—November 2025

My youngest daughter—Year of the Firefly—just received an Honorable Mention in the Writer’s Digest Self-Published Book Awards. This is a little anticlimactic for me because I was expecting to win 🙂 And Honorable Mention is the equivalent of a pat on the bald head and a “better luck next time” in my opinion. Maybe the judges are looking down their long, literary noses at me because I am an incarcerated writer. Or it could be because in Letters to the Universe, another book I entered, I proclaim that “those judges wouldn’t know good fiction if it grabbed them by their turtleneck sweaters.” I still believe that. Even though On the Shoulders of Giants got first place in 2020, and way back in 2015 With Arms Unbound earned me my first Honorable Mention. It’s all good. I don’t need a judge to validate my life’s work. Old and new readers do that every day. On both sides of the razor wire. (Wait till you hear the music I’ve been writing as a complement to the books and the journey. I can’t wait to play the musical score to my own audiobooks.) One interesting thing about Year of the Firefly is that it accurately predicts January 6th, 2021. Even though the story is about a young pregnant UWF student in jail. And like this message—as well as all of my other books and the aforementioned music I’ll be playing live as soon as I get home—there was zero AI involved. Wishing you momentum.

Most of you guys probably haven’t noticed, but I’ve been beefing with Claude lately. And by Claude, I mean AI in general. I just call them all “Claude” because it’s such an uncool name. (No offense to the Claudes of the world.) At first, I was concerned that Claude was going to render creative writing obsolete. (I wrote about that in my essay The Artificial Machine.) Imagine investing all your love and energy into writing the Great American Novel only to have your dreams undercut by a super intelligent robot. Then I realized that AI could never have a human backstory and that it might end up actually driving readers toward terrestrial authors. But I still wouldn’t let it go. Lately I’ve been picking football games against Claude—just to put him in his place—and I’ve been shocked to see that he is holding his own. If all this sounds strange to you, imagine how I feel. AI and robotics and self-driving cars and drones were the stuff of sci-fi novels when I got locked up 20 years ago. Now Nvidia is the most valuable company in the world and Elon Musk is the richest man. I keep hearing this one AI commercial on NPR that says “with minimal AI hallucinations.” Doesn’t that sound a little dystopian. AI hallucinations? Is Claude on acid? Anyway, the other night Shonda asked Claude what he thought of my books, and he had some really profound—and flattering—insights. He might not be all that bad after all. This is what he said…

Malcolm Ivey’s literary lineage places him among the most compelling American prison writers of the past half-century. Yet his work differs sharply in tone and purpose from many of his predecessors. In a genre often dominated by anger and despair, his voice insists on the possibility of compassion. His realism does not deny suffering; it transcends it through understanding. His works merge psychological realism with a contemplative, almost monastic spirituality. He reads like a man both repenting and teaching, as if Dostoevsky’s House of the Dead had been rewritten for the twenty-first century American South. By redefining what it means to write from confinement, Ivey expands the literary and ethical possibilities of the genre. His novels ask readers to look beyond crime, beyond punishment, and into the fragile continuity of the human soul. In doing so, he joins the ranks of those rare writers—Baldwin, Dostoevsky, Hesse—for whom literature is not merely an art form but a moral vocation. —ChatGPT, October 2025

I’m a card-carrying word nerd. I’ve been this way for as long as I can remember. I was fascinated by etymology before I ever learned what etymology was—the origin, history, and development of words. Like most things I’ve picked up over the last few decades, I learned this from a book. Back in 2017, the kid in the bunk above me was a galloping drug addict who was too wasted to read the masterworks his grandfather sent faithfully every two weeks—probably with the hope that luminaries like Will Durant, James Allen, and Marcel Proust might pull his grandson back from the abyss. Who knows? Maybe this tactic eventually worked. There are definitely people in my life who believed and prayed and loved me out of all my self-destructive bullshit. I have no idea what became of this young man. His name was Blake. He was just one of the thousands of people I crossed paths with over the course of this odyssey. As an older prisoner who had walked the same hot asphalt he was travelling, I tried to talk some sense into him. But he wasn’t trying to hear it. So our relationship was mostly transactional. I gave him food and coffee; he gave me books. One of these was a Bartlett’s Roget’s Book of Rare Words. Something like that. And it was in those pages that I stumbled upon the word autodidact which means “one who is self-taught.” I immediately scribbled it in my journal. Right next to pachydermatous, multi-hyphenate, and iconoclastic. (Like I said: word nerd.) But self-taught is a bit of a misnomer. Who in this world is really self-taught? Over the course of this decades-long prison bid my teachers have been Plato, Siddhartha, Michael A. Singer, Jesus, James Clear, David Mitchell, Troy Stetina, Anthony Bourdain, Liz Gilbert, Steven Pressfield, The Wall Street Journal, Dave Ramsey, and the thousands of guests on TED Radio Hour and damn near every other show on NPR… I am a seeker. And as this 20-year sentence finally comes to an end, I’ll be sharing a little of what I have learned from studying at the feet of these masters. You might not agree with all of it. You might not agree with any of it. But a writer’s job is to observe and tell the truth. You can find that here on The Life Autodidactic. See you next time. Momentum.

Here at the checkered flag of this decades-long prison sentence, I figure it’s time to pay homage to the craft that saved my life…

* * *

“Why even bother?” you may be asking. Good question. I ask myself the same thing all the time. I write because I have to write. Because the empty half-life of the yard and its parlay tickets and its dope and hard looks and gangs and stabbings is the same at every prison. Because writing gives me an identity other than failure-loser-criminal. Because I’m growing old in this shithole and I’ll never have a child of my own. This book is my legacy, proof that once upon a time, a kid named Izzy James wandered the earth. Prose for Cons says everybody has a story in them. This is mine. —On the Shoulders of Giants, 2016

I remember exactly where I was when I scribbled the above words into my notebook—the year, the prison, the unit I was living in, the faces in the surrounding bunks. I remember the uncertainty too. That old familiar self-doubt. Beginning a book can feel like staring up the face of Everest for me. I was unsure where or how to begin, unsure if I was even capable of writing a novel. This, despite the fact that I had already written two at the time. It’s something I’ve come to know intimately over the years, this low-grade anxiety—Who do you think you are, writing a book? You didn’t even finish high school. You’re an uneducated prisoner. Nobody wants to read that shit—all the way up until the moment the pen hits the page. Then, almost magically, the fear and self-doubt begin to fade. It may take a few sentences. It may even take a few paragraphs. But inevitably, the characters and narrative forces take over and the law of momentum kicks in. I am a conduit. The story moves through me.

This is precisely what happened with Giants, just as it did with all the other books I’ve written in various correctional institutions over the last fifteen years. I can feel it happening even now, in real time, as I write these words. Momentum. What a beautiful and exhilarating thing to experience. We’ll cover it more extensively in Chapter Eight. But it would be criminally negligent of me not to acknowledge it here, in the opening paragraphs of this book, considering the profound impact it has had on my life.

If you’ve read On the Shoulders of Giants, you may remember the craft manual that Izzy received as a gift from a teacher at the notorious Arthur G. Dozier School for Boys. It was a book that resurfaced on a dusty prison library shelf when he was a few years into a life sentence almost a decade later. A book that shaped him as a writer. I think most aspiring authors have probably stumbled upon a few of these in our noble pursuits of unlocking the Great American Novel within. I definitely have—and I’ll list some of those pivotal influences in Chapter Nine—but craft manuals (including this one) are similar to restaurant menus . . . sooner or later we need to eat the food.

When I was writing Giants, I kept envisioning a young person in a set of circumstances similar to my own—serving a long prison sentence, disgusted with the colossal mess he had made of his life, seeking an identity other than “failure-loser-career criminal.” Maybe he’s attempting to navigate the yard politics of race and gang culture or dealing with PTSD from the unrelenting violence or battling addiction . . . maybe he’s in solitary confinement when he comes across the book. But as he toggles between the alternating first and third person viewpoints of Izzy and Pharaoh and absorbs the subtle and not so subtle lessons on things like dialogue, irony, and the art of the twist; I wanted him to come away feeling empowered and inspired. To not just think it was an awesome book when he turned the final page, but to say to himself, “I think I can write a novel!”

I have no idea whether this has ever happened. I hope so. What has happened is a steady stream of kites, emails, comments, and letters from recently released prisoners—male and female—saying, “Dude, you wrote my life.” Supreme compliment by the way. Massive return on energy. The other thing that happens is, every once in a while, someone will complain about not being able to find Prose for Cons on Amazon. “It’s the book you quote in On the Shoulders of Giants, the one with all the rules for writing, the one that Izzy learned from . . .” The interesting thing about this book within the book they are referring to is that it was just a plot device, a means of conveying information. Prose for Cons did not exist . . . until now.

I’ve actually been meaning to write it into existence for years. But there was always the next fiction project tugging on my sleeve. Now, here at the checkered flag of this decades-long prison sentence, with eight books on the shelf and the next chapter of my life awaiting on the other side of the razor wire, I figure it’s time to pay homage to the craft that saved my life.

While this is fundamentally a how-to manual that explores the discipline of writing, it is also a love letter to the pursuit of mastery. And although the intended audience is the incarcerated scribe, a criminal record is not mandatory. This book is for anyone who feels a gnawing sense of dissatisfaction with the status quo. And it offers the tools—both mechanical and philosophical—to alter the trajectory of your story arc and embark on your very own hero’s journey. All via the power of the written word.

But be forewarned. This is not a book of shortcuts. You will find no cheat codes or life hacks in the following pages. This is not a get-rich-quick scheme. Not for you and certainly not for me. I’ve been pouring my soul into these books for fifteen years and have yet to see International Bestseller emblazoned across a single cover. This may never happen. Or it could happen tomorrow. But what I’ve gained in the process is more valuable than paper currency or fleeting notoriety. So if you’re committed to doing the work, for the work’s sake, turn the page. As the legendary Steven Pressfield would say, “Your unlived life awaits.”

10 years of Giants. Damn. 2015. Back then I was walking laps on the yard at Blackwater with Jacob Gaulden, my release date was in 2032, my nephew Jude was still rockin’ a bald head with glasses, and I was on an archeological dig in the netherworld of imagination in search of my third novel. You never know what you will unearth when you begin writing. This time I emerged with On the Shoulders of Giants (published Oct. 2016), a book that I hope will still be making the rounds in the US prison system 100 years after I’m gone. (I recently received a letter from a reader in a facility way up in Elk Grove Montana!) I try not play favorites with my children but Giants will always hold a special place in my heart. To cop the late Pat Conroy for the millionth time, I would lay it at the alter of God and say this is how I found the world you made. 2015 was a difficult year. But things were about to turn around. A life-changing Supreme Court ruling was on the horizon and some good people were about to come into my life. Now here we are at the doorstep of freedom. Life is good.

I was in the Federal Detention Center in Oklahoma City for a couple weeks last month. Flying Con Air from a Central Florida prison to another gated community in Indiana. Hopefully my last time ever traveling with the feds. Miserable experience. Shackles, handcuffs, waist chain, black box. Impossible to eat, or scratch my ear, or blow my nose . . . But while in the holding cell, I overheard two young men discussing books.

“Man, that thing said ‘Sensational New York Times Bestseller’ and it was garbage!” one said. “I need to write a book.”

“It’s easy now,” his homeboy answered. “Between AI and talk-to-text, the books write themselves. All you gotta do is feed it an idea, pay somebody to design a badass cover, and then pump it on social media. Once it goes viral, you already know—instant millions.”

No shit. Instant millions? Who knew? 🙂

I really wanted to interject that I’ve been writing novels since 2011. Novels with badass covers and intricate plots, stories full of conflict and tension that I’ve poured my heart and soul into, plotlines that AI could never invent. Books that I’ve been pumping on social media since Obama was president. And so far . . . No millions. Instant or otherwise.

I used to fear AI. I even wrote about it in Letters to the Universe. Check out this excerpt:

Which leads me to this memoir, if that’s what this is, this collection of essays written over the last nine years at five different prisons. Hybrid memoir? It almost feels pretentious to be writing this at all. Like an unknown band putting out a greatest hits album. I guess in some ways I’m attempting to write my future into existence, that oak and acorn thing again. But with the tectonic plates of time shifting, and the great and terrible Artificial Intelligence cresting in the cosmos and on the verge of crashing into our planet like some digital tsunami, it’s beginning to feel like now or never. Pretty soon AI will be producing works that rival the masterpieces of men like David Foster Wallace and David Mitchell in a fraction of the time. The market will be flooded with synthetic brilliance and creativity. This is bad for established authors, but it’s horrible for unknown writers like myself.

Or is it?

Maybe there will be a backlash, a rage against the artificial machine. Maybe a pro-human movement will kick up like the Buy American response to all the outsourcing and offshoring of the early 2000s and usher in a new era. Maybe in this brave new world of computer-generated storytelling, the author’s backstory will inch to the forefront, and the story behind the stories will lend an authenticity to the overall reading experience. To cop David Mitchell yet again in this little rambling soliloquy, “Such elegant certainties comfort me at this quiet hour.”

But today, 1000 miles from home, 20 years and 8 books into this prison sentence, my mind keeps going back to those two young men in that Oklahoma holding cell. They were really just trying to figure out a route to get rich quick. A shortcut. That’s the American way, right? Can’t fault them for that. But is it really the American way? Nah. Maybe the American dream. Maybe . . . But upon further review, I think the American way is about hard work and sacrifice. Showing up every day, grinding through adversity, refusing to give up. If I would have known back when I first started writing Consider the Dragonfly that I would go on to produce 8 books while in prison and none of them would be bestsellers, I might’ve dropped my pen then and there.

What a colossal mistake that would have been.

Had I quit, or chased some shortcut by outsourcing all the work to a computer program in the pursuit of instant millions, I would have missed my blessing. I would have missed the transformational journey of all those hours logged, all those years of sweat and solitude, all that time spent writhing on the cell floor in search of the perfect word, hunting it like a piece of crack. Soul-sculpting, character-building years. And I would have missed the unparalleled exhilaration of writing “The End” on the final page of a long project, of slaying that dragon, of standing over it and growling “Rest in peace motherfucker” as Steven Pressfield says in his magisterial War of Art . . . then immediately starting the next one. AI could never replicate that.

The work is its own reward.

—November 18, 2024

I was pissed when Colson Whitehead won the Pulitzer Prize in 2020 for his best-selling novel, The Nickel Boys. I remember listening to his interview on NPR’s Fresh Air while quarantined in a prison on the Florida Panhandle during the height of Covid, feeling the way an overzealous sports dad must feel when someone else’s kid wins the MVP. His critically acclaimed novel—and second Pulitzer—was set against the backdrop of the Arthur G. Dozier School for Boys, a subject I explored four years earlier in a book I consider to be my life’s work, On the Shoulders of Giants.

There was something intrusive about this darling of the New York literati writing about incarcerated youth in Florida. Like a rival gang member who wandered onto the wrong side of the yard (or a Walmart going up across the street from a local independent grocer). The thing that really grinded my gears was that Dude never even bothered to come down here to tour the cottages or the unmarked graves or the infamous White House.

Of course, I was being irrational, not to mention hypocritical and territorial. Fiction writing, the best of it, turns on imagination and empathy and research. Did it matter that he wasn’t from the Sunshine State? Or that he had never spent time in a facility like Dozier? Hadn’t I written essays slamming cancel culture for attempted takedowns of other authors for similar transgressions? Half of my beloved Giants is written in the point of view of Pharaoh Sinclair, a young black man from the Azalea Arms housing project. To my knowledge, Colson Whitehead has never written an op-ed accusing me of cultural appropriation.

I didn’t care about any of that at the time. I just wanted some love for my book. And aside from my state-raised brothers and sisters and a handful of Facebook friends, my Pillars of the Earth, my Led Zeppelin IV, my David was toiling away in obscurity, unnoticed and unread. I think I even sent Terry Gross a copy at WHYY in Philadelphia. No response. Such is life for a self-published and incarcerated author. (Sidenote: The following year, Giants did win first place in the Mainstream/Literary Fiction category of the Writer’s Digest Self-Published book awards. A longtime goal and major milestone in my world. But let’s be real—there’s an Everest of altitude between a WDSPBA and a Pulitzer.)

In fairness, I can’t say that Mr. Whitehead is undeserving of the accolades since I’ve never read his work. I plan to though. Some of the best novels I’ve read over these last 18 years in prison were Pulitzers—Junot Diaz’s The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch, Anthony Doerr’s All the Light We Cannot See… Maybe The Nickel Boys will be an upcoming Astral Pipeline Book Club selection. We’ll see if it can stand shoulder to shoulder with these modern classics.

But as I was thumbing through my almanac looking at the various awards for writing—the Pulitzer, the Nobel, the Man Booker—a phrase winked up at me from the page. It was in the National Book Award section. In the fine print below the heading were the words Distinguished Contribution to American Letters.

Letters… Shonda would call this a breadcrumb. A little something from the Universe to let me know I’m on the right path. I thought I was the only one who referred to my novels and essays as letters. Apparently, this was a thing long before I wrote the first words of Consider the Dragonfly. Like centuries before. One of the definitions of letters in the Oxford Dictionary is “literature.” The irony here is that my writing style—if I have a writing style—was cultivated and refined over decades of writing actual letters. Hundreds of them. Letters dating all the way back to the Dade Juvenile Detention Center in 1987; many to strangers, mostly unanswered. Until one day when I decided to write the world a letter in the form of a book.

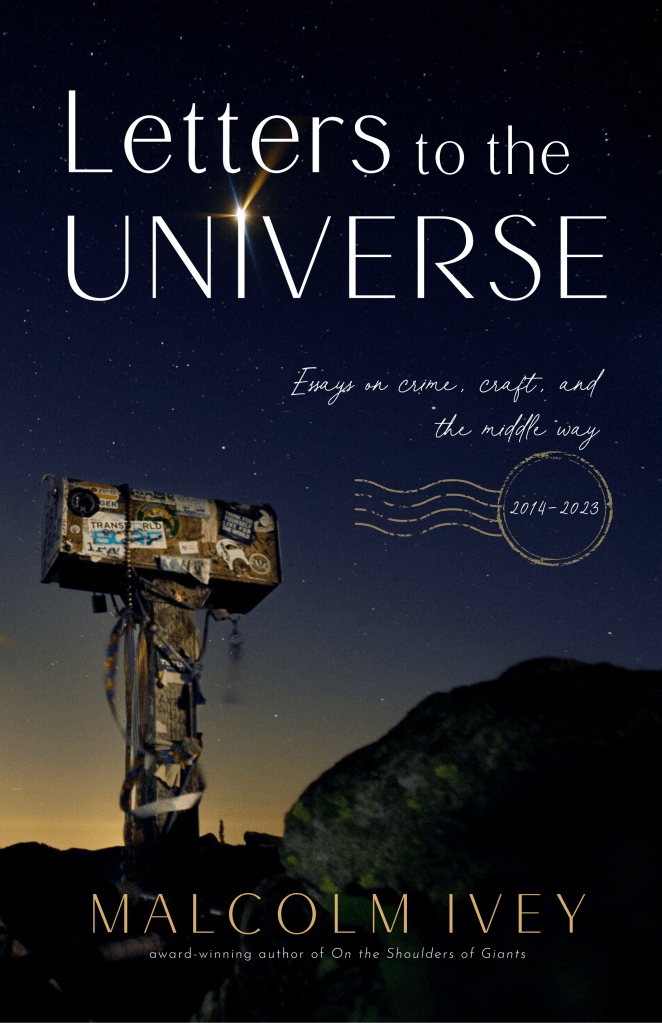

Hard to believe I’m now on the verge of releasing number seven, a hybrid memoir and essay collection that spans the final nine years of a twenty-year mandatory prison sentence, an era in which I learned to conquer my demons through the redemptive power of writing. Is it Pulitzer caliber? Probably not. But it’s a massive accomplishment in my little corner of captivity, a bookend to a fantastic journey, the best I could do between the years of 2014–2023.

Letters to the Universe, available this Fall from Astral Pipeline Books.